Welcome to the 2024 Christmas issue of Fanning the Flames. We missed the September issue so we are excited to share what’s been happening at Bonfire HQ. We wish you a Merry Christmas and happy new year celebrations for 2025.

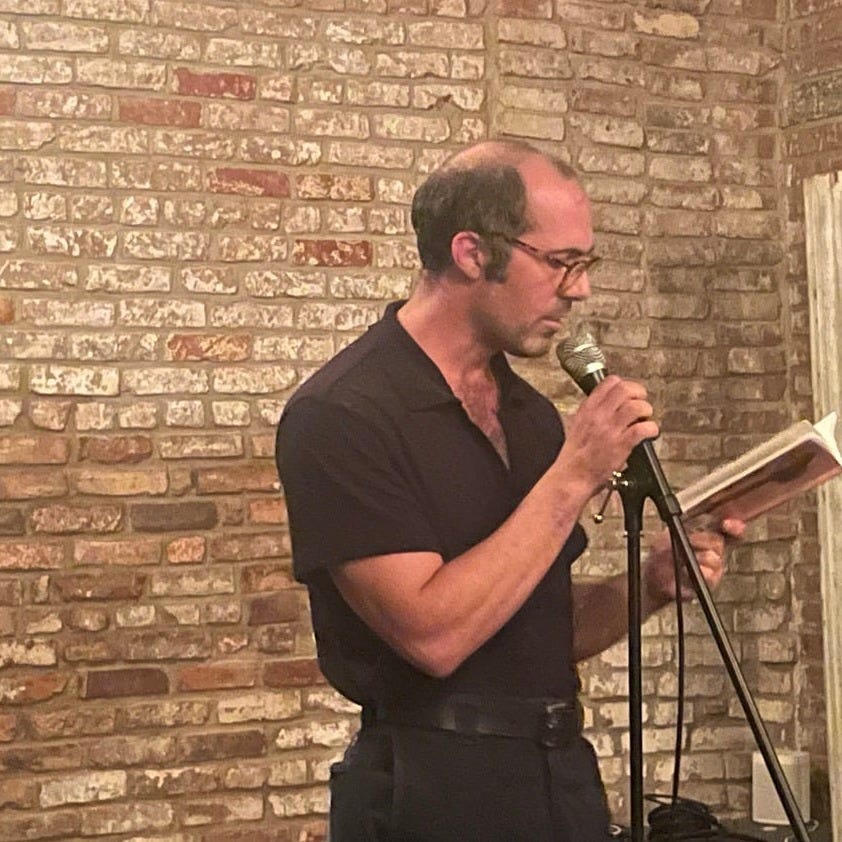

Caleb Caudell, Sovereign House, New York

This month’s issue comprises:

1. Announcements:

Hardly Working released!

The Literate Detective by Paul Scully (March 2025)

Ryan Daffurn book postponed

Submission window: January 1-31

Spare Us Yet by Lucas Smith (Wiseblood, June 2024)

2. Leisure: The Basis of Culture. Review by Andrea Jonathan

Announcements

Hardly Working: A Semi-Auto Fiction, the genre-bender by Caleb Caudell was released in September. The book was launched at Sovereign House, New York City. The New York critics love it. Caleb was interviewed at length by Ross Barkan at his excellent Substack, Political Currents. There was also a nice review by Jonathan Mittiga in RealClearBooks. Hardly Working is a stylistically unique book that portrays a way of life that the broader culture is just starting to notice. It makes excellent Summer beach reading or Winter fireplace reading.

Advance praise is in for Paul Scully’s forthcoming fourth poetry collection, The Literate Detective and Other Crimes. Judith Beveridge, a Prime Minister’s Award-winning poet, writes,

Paul Scully’s poetry reveals an astute and curious mind able to penetrate both the light and dark of human morality. Whether revealing the details of gruesome crimes or the tender devotions of an elderly couple, Scully invents stunning images and phrases which immerse the reader in unexpected scenarios and complexly imagined personae. His work is buoyed by wonder and compassion, by metaphorical richness rarely matched by other contemporary poets. In all these engaging, wide-ranging poems, there is a deep commitment to poetry’s ability to perpetually renew insight and knowledge.

Dimitra Harvey, author of A Fistful of Hail (Vagabond, 2018), writes,

Scully shapes language like a master lapidarist cuts stone: his intricately faceted metaphors dazzle. From the ‘swaddling ambivalence’ of an opening suit that traces the evolution of a budding criminal detective, to chilling portraits of the criminally insane, and glistering studies of everyday aberrations of the mind, it’s impossible not to partake in the poet’s sheer delight in his craft. The collection shifts to high art, where ‘there is a tidal zone / pigment between thought and brushstroke,’ and tender suburban fables that are ‘vigil for the impaling moment… / a crescendo of awareness…’. I couldn’t resist phrases like ‘the hour soon dwindles into fractions of itself’ and ‘Hope’s brain centre… / resides north of the liver, south of Heaven…’. Scully’s poetry is polyhedral, a dexterous geometry that is a joy to study and return to.

We are extremely excited for this book. You can find more information about Paul here. Release date: March, 2025.

Ryan Daffurn’s art book has been POSTPONED. We are now expecting to release the book in May, 2025. Ryan recently held a packed and buzzing gallery opening at Maunsell Wickes Gallery in Sydney. Bonfire was in attendance and greatly enjoyed the gallery’s hospitality. The exhibition showcases Ryan’s recent work from his time at Hill End, one of Australia’s iconic art locations. This work will make up the bulk of the forthcoming book. You can view Ryan’s recent show here and I must say that viewing the works online versus in person is like the difference between an American cheese square and a nice Camembert.

Submissions open January 1! Our submission window will open on January 1 and close on January 31. Send us your best fiction, poetry, and non-fiction. Full guidelines can be found here. We are also open at any time for pitches for the new Bonfire Monograph series. More news on this will come soon.

Some exciting news on a personal front for Lucas. Our older brother in indie publishing, Wiseblood Books, (check out their excellent list here), will publish Lucas’ debut collection of stories, Spare Us Yet, in June 2025. More information and a video of Lucas reading from one of the stories can be found here.

Merry Christmas to all and we will see you in the New Year. Email correspondence will be paused until the 15th of January.

To purchase Bonfire titles please visit our website.

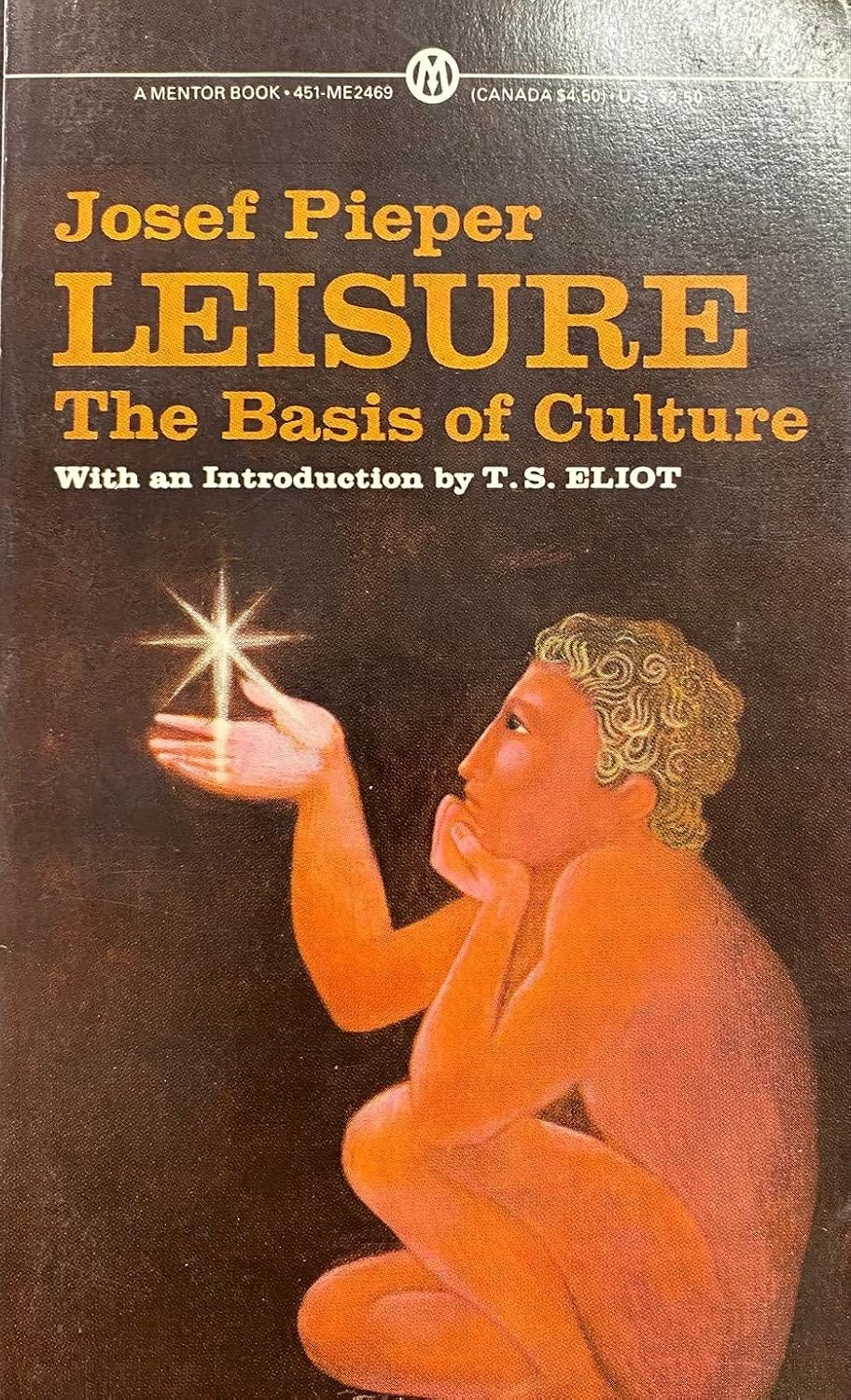

Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948)

by Josef Pieper trans. Alexander Dru

Review by Andrea Jonathan

As children, we are naturally imbued with a sense of play. Work is something usually we are cajoled into doing with threats or bribes, and it takes a substantial amount of conditioning to see work as something that is a source of meaning, identity, virtue or belonging. Childhood and adolescence is increasingly seen as a preparatory phase for the world of paid employment, with both schools and universities clamouring for recognition for producing ‘work-ready’ graduates ready to face contemporary ‘challenges’ which presumably relies on the mystical foresight of wisened deans and headmasters not normally known for their predictive capabilities. Despite legislative attempts to limit the intrusion of work into our lives after hours and social media trends such as ‘quiet quitting’, the age of ‘total labour’ as described by Pieper, has well and truly arrived.

This book contains the text of two essays delivered by the German philosopher Joseph Pieper in Bonn in 1946. The first, which I am mostly concerned with, addresses the 20th century’s notion of the social role of work with reference to the Aristotelian and Thomistic concepts of leisure, and the Greek view of contrasting servile work and liberal arts.

“Leisure, it must be clearly understood, is a mental and spiritual attitude—it is not simply the result of external factors, it is not the inevitable result of spare time, a holiday, a weekend or a vacation. It is, in the first place, an attitude of mind, a condition of the soul, and as such utterly contrary to the ideal of “worker” in each and every one of the three aspects under which it was analyzed: work as activity, as toil, as a social function.

Compared with the exclusive ideal of work as activity, leisure implies (in the first place) an attitude of non-activity, of inward calm, of silence; it means not being “busy”, but letting things happen.”

Pieper seeks to remind us of the overvaluation of the sphere of work, and how what is truly human derives not from toil. In the present day, even leisure itself has been commodified into tourist or wellness ‘experiences’ which serve to produce more productive workers after their expensive treatments or holidays, ‘recharging batteries’ for the next set of hurdles. Are we missing out on something deeper, which cannot be simply derived from a process but rather must be divined with unstructured time and open space?

“Compared with the exclusive ideal of work as toil, leisure appears (secondly) in its character as an attitude of contemplative “celebration”, a word that, properly understood, goes to the very heart of what we mean by leisure. Leisure is possible only on the premise that man consents to his own true nature and abides in concord with the meaning of the universe (whereas idleness, as we have said, is the refusal of such consent). Leisure draws its vitality from affirmation. It is not the same as non-activity, nor is it identical with tranquility; it is not even the same as inward tranquility. Rather, it is like the tranquil silence of lovers, which draws its strength from concord.

Pieper avoids the turgidity and recursion often attributed to German philosophers, and I found him to be very readable. He is unafraid to confront the managerial philosophies inherent to both Western and Soviet regimes and their educational doctrines:

“In a consistently planned “worker” State there is no room for philosophy because philosophy cannot serve other ends than its own or it ceases to be philosophy; nor can the sciences be carried on in a philosophical manner, which means to say that there can be no such thing as university (academic) education in the full sense of the word”

Given that contemporary discourse is overwhelmingly focused on ‘solutions’ to contrived problems, it behooves some of us to take a step back and consider philosophically whether we can be saved from being mere ‘functionaries’ and workers at the expense of all that is good, true and beautiful. How can we, as a society, or as individuals resigned to the state of society, deproletarianise ourselves in unfettering ourselves from the vast utilitarian process that is all-consuming and squandering the precious resources of our planet? These are the questions posed by Pieper, to which he offers several humble solutions. I will leave it the rest to you to find out if you are so inclined.

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from the team at Bonfire HQ.