Fanning the Flames · Issue #11

Welcome to another month of Fanning the Flames. As the year draws to a close, we hope you are well and have exciting things planned for the holidays. Fanning the Flames will take a break in December but will be back in January. This year was another of strong growth for Bonfire Books. We had our first ever award shortlisting: Caleb Caudell’s The Neighbor (2021) was shortlisted in the Debut category of the Indiana Author Awards. We added three new living authors to our list in Alasdair Cannon, To Giang and Clarence Caddell and held a grand total of four launch parties. A warm thank you to everyone who supported us this year in big and small ways and we look forward to an even better 2023. A reminder that our books make excellent gifts for the readers in your life this Christmas season.

To order titles from our catalogue please visit bonfirebooks.org

This month’s issue comprises:

1. Announcements:

An Illusion of Division by Father Lawrence Cross to be launched at 5pm, January 17, 2023 at the Venerable English College, Rome, Italy.

2023 Titles

Poetry Anthology submissions

New addition to the Bonfire team

2. The Drums of War, Editorial by Andrea Jonathan

3. Die Skatspieler (The Skat Players) by Otto Dix: A Digital Exhibition by Charlotte Walkling

4. Redeployment (2014) by Phil Klay & Breakfast With the Dirt Cult (2012) by Samuel Finlay, review by Lucas Smith

Announcements

You are warmly invited to the launch of An Illusion of Division by Father Lawrence Cross to be held at 5pm, January 17, 2023 at the Venerable English College, Rome, Italy. Father Cross’ book is a detailed study of the “Dialogue of Love” that transpired throughout the 20th century between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches. The book asks major questions concerning the ongoing division of the two largest forms of Christianity, always with an eye to their essential unity, concluding that the nearly thousand years of schism may in fact be illusory

.

2023 Titles: In addition to our inaugural poetry anthology we are happy to announce some of the titles we will publish in the first half of next year:

Pinter’s Son Jim (1897) by Henry Lawson. The only full-length dramatic work of that most recognisably Australian of writers, Henry Lawson produced, Pinter’s Son Jim is a classic tale of an outback town, told in Lawson’s sentimental style. It features corrupt miners, pub jesters, a seemingly hopeless romance and a broad cast of red sand archetypes. Never staged in his lifetime, and previously available only in old and bulky complete works, this marks the first ever stand-alone publication of what should rightfully be an Australian theatrical classic.

The Gringai of Port Stephens (1929) by William Scott. William Scott grew up in Carrington, a suburb of the port city of Newcastle, NSW and catalogued a series of observations of the people of the Gringai tribe, who once inhabited the lower portions of the Hunter and Karuah river valleys. In his own words:

The lads of the tribe were my playfellows. I learned to speak their language with a degree of fluency as did my sister to a greater extent - and we mastered those difficult labials that few white men have been able to catch correctly, as is evidenced by the discordant corruption of the many beautifully euphonious native names.

To quote further, from the introduction by the original publisher, Gordon Bennett:

I felt that I had been afforded the opportunity of contributing something of especial value to the scant store of literature that deals with the lives and customs of the earliest inhabitants of a little known, but historic, part of New South Wales. It is with the hope the public will appreciate the recording of facts that might otherwise have gone unnoted that I present this booklet to the world.

The booklet is now one of the only remaining primary sources of Indigenous Australian history of the area and out of print for nearly a century. We seek to uphold the intentions of Scott and Bennett in restoring this text and making it available again in print to the public.

Albany Unravelled by Steffan Silcox and Douglas Sellick. This monumental work that expands and corrects the historical record was compiled and written to commemorate the upcoming Bicentennial of one of the nation’s most historically significant regional towns in 2026. Albany Unravelled will be published in mid-2023. In their foreword to the book, Professors Stephen Foster and Peter Spearritt write:

Douglas Sellick and Steffan Silcox have put in a prodigious amount of effort in assembling these documents, along with explanatory commentary. Both authors live in Albany and manage to convey their fascination with its rich history. They have gone to great pains to check some of the key claims about Albany’s history, often taken for granted by generations of historians, not always going back to the original sources. So, this book will stand as a well-researched collection for many years to come.

Australian Poetry Anthology: Call for Submissions. The deadline has now been extended to the 15th of December 2022. If you are yet to submit, or know a fellow poet who may be interested in submitting, please note this deadline extension. Guidelines below.

Thanks to a grant from the English-Speaking Union (Victoria Branch) Bonfire Books will showcase the finest in contemporary verse in early 2023.

Submission Guidelines

Please send up to 3 poems in a .pdf, .doc or .docx attachment to info@bonfirebooks.org. with “Your Surname-POETRY” in the subject line. Poems should be no more than 100 lines each and no more than five pages per full submission. Poems may be previously published in periodicals within the last five years but not in books. Poets will be remunerated and will receive a copy of the anthology. While all poetic forms and themes are welcome, preference will be given to music, sense, meaning and felicity of language. Submissions close on the 15th of December and are open to Australian citizens and Australian residents.

In November we welcomed Charlotte Walkling to the Bonfire Books team as Administrative Assistant. Charlotte read history and French at Melbourne University and is helping to prepare new titles and launches in 2023.

The Drums of War

Editorial by Andrea Jonathan, Creative Director

A brief glance of the headlines is enough to remind one that war continues to be at the centre of public attention. Trench battles between Ukraine and Russia, the growing prospect of confrontation with China, ongoing cyber espionage between Eastern and Western powers and the series of unending conflicts in the Middle East together signal an end to the pax americana that began to slowly unravel in the 1990’s.

“To see human beings in agony, to see them covered in blood and to hear their death groans, makes people humble. It makes their spirits delicate, bright, peaceful. It's never at such times that we become cruel or bloodthirsty. No, it's on a beautiful spring afternoon like this that people suddenly become cruel. It's at a moment like this, don't you think, while one's vaguely watching the sun as it peeps through the leaves of the trees above a well-mown lawn? Every possible nightmare in the world, every possible nightmare in history, has come into being like this.”

― Yukio Mishima, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

War is a subject of great literary inspiration. It brings to the surface fundamental questions about life and death, the human condition, and the contradictions of morality. Waugh, Hemingway, Jünger, Heller, Vonnegut, Mishima are but a few literary giants who contemplated the devastation of modern warfare and its effect on man and society. If there can be said to be a winner of any war, it is less the victors than the writers and readers of literature.

“I came to realize that one single human being, comprehended in his depth, who gives generously from the treasures of his heart, bestows on us more riches than Caesar or Alexander could ever conquer. Here is our kingdom, the best of monarchies, the best republic. Here is our garden, our happiness.”

― Ernst Jünger, The Glass Bees

What is highly concerning is the glib way that war has come to be portrayed and understood. Rather than the both sobering and terrifying understanding of war that some of the aforementioned 20th century novelists portrayed in their works, the public is treated to triumphant and propagandistic coverage of foreign conflicts by po-faced journalists working for corporate and state media conglomerates, alongside social media personalities and ‘influencers’ who peddle their own form of self-interested commentary. The fact that none of us are immune from propaganda should be cliché; sadly it isn’t.

“For Guy the news quickened the sickening suspicion he had tried to ignore, had succeeded in ignoring more often than not in his service in the Halberdiers; that he was engaged in a war in which courage and a just cause were quite irrelevant to the issue.”

― Evelyn Waugh, Men at Arms

Iraq, Bosnia, Serbia, Afghanistan, Iraq again, Libya, Syria, the ‘too close for comfort’ eastern front of the Ukraine, with the added spectre of nuclear Armageddon – their images on the screen form an endless reel of footage that begets an ever changing series of ‘takes’ of what to think and feel, right up to the latest minute of syndicated Associated Press updates. I ask myself, where would the charismatic and erudite Christopher Hitchens, pro-war apologist and darling of the American press, stand today, had he lived long enough to bear witness to the last decade? His fellow-travellers and their editors can’t hide under gravestones and continue to be published yet their retractions and apologies are nowhere to be found.

As Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ turned out to be a brief and illusionary spell, all of us must come to terms with the reality and meaning of war. This state of affairs is not new, but rather a return to history. At Bonfire we hope to bring back to the present some of the memories of those who can illuminate the truth of war and what it says about who we are. Perhaps then we can extend our collective memory long enough to avoid it, and if not, survive it.

Die Skatspieler (The Skat Players) by Otto Dix: A Digital Exhibition

by Charlotte Walkling, Administrative Assistant

After a summery four month jaunt around Europe, I returned to Melbourne and began to reflect on my travels. The city I visited that eluded me the most was Berlin. The concrete city’s sad history ricocheted off every building - I could not escape it. I had heard Berlin to be exciting and electric. Even though I searched for these colourful pockets I could not find them. Perhaps I did not search hard enough.

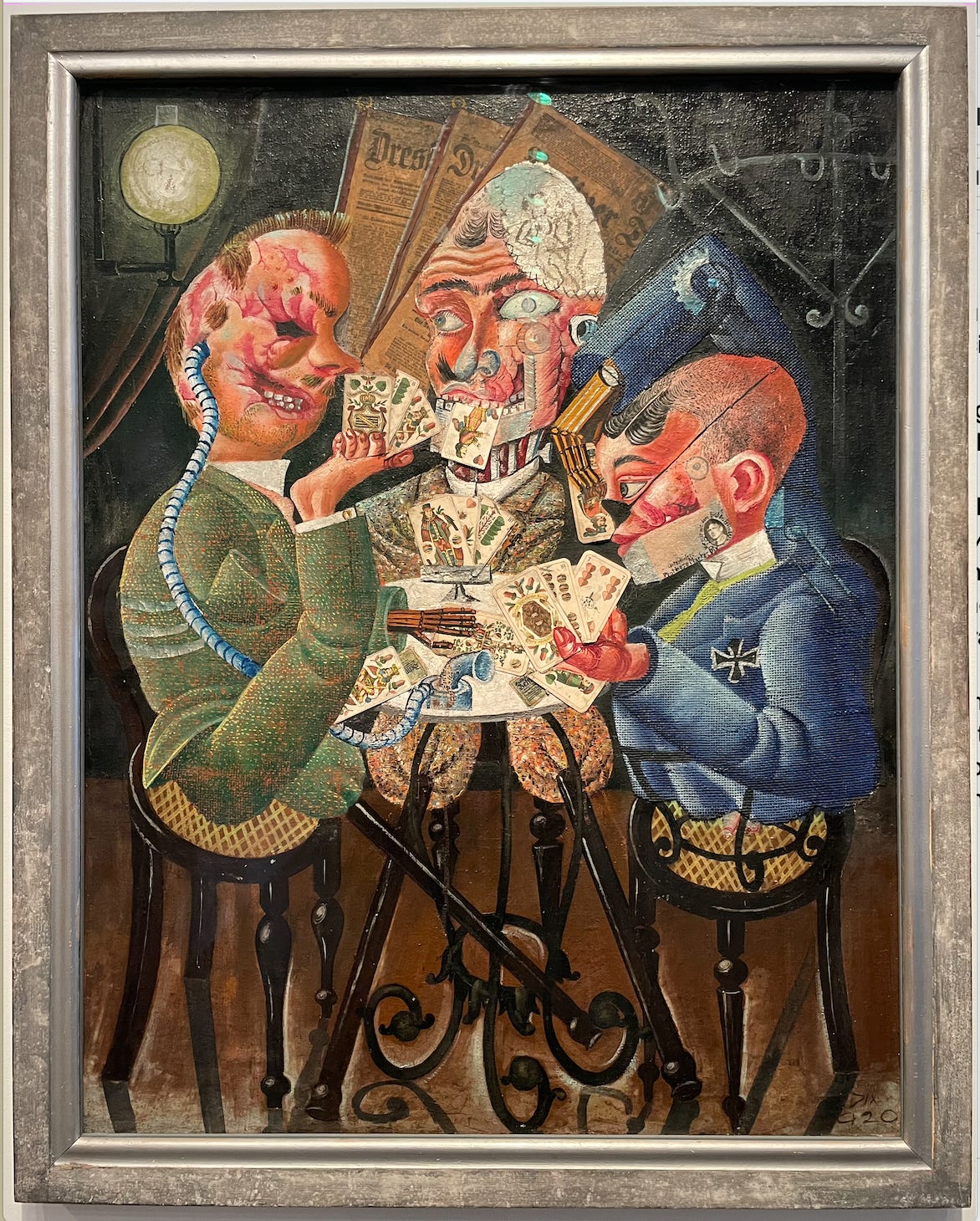

However, after visiting many galleries throughout Europe, the exhibition that stuck with me the most was The Art of Society 1900-1945: The Nationalgalerie Collection at the Neue Nationalgalerie. One piece entitled Die Skatspieler (The Skat Players) I found to be particularly mesmerising. With Remembrance day having just passed us by, the piece depicting three disfigured World War One veterans has once again popped into my mind.

The piece is by Otto Dix, a German artist known for his ruthlessly realistic depictions of war and German society during the Weimar Republic. Dix’s pieces fill some of the World War One aspect of the exhibition which focuses on the social processes of Germany’s historical and political affairs, of which Berlin has always been the centre.

Die Skatspieler (The Skat Players), 1920

Sturmtruppe geht unter Gas vor (Shock Troops Advance under Gas) from Der Krieg (The War - Dix Engravings), 1924

Kriegskrüppel (War Cripples), 1920

Redeployment (2014) by Phil Klay & Breakfast With the Dirt Cult (2012) by Samuel Finlay

Review by Lucas Smith, Editor-in-Chief

The publishing industry, like war, is fickle. Two books treating the same subject matter in a similar way can have vastly different fortunes depending on factors other than depth of vision, like two soldiers on the same patrol—one of whom is blown to pieces while the other emerges unscathed. Two recent books by American war veterans that draw heavily on their experience in Middle Eastern theatres of war illustrate this phenomenon. Redeployment, a collection of twelve stories by Phil Klay, won the USA’s National Book Award in 2014 and features a blurb from Barack Obama on its cover. Breakfast With the Dirt Cult, self-published in 2012, currently has a 4.5 star rating on Amazon based on some 120 reviews. Redeployment enjoys the same star rating and ten times the number of reviews.

Both books are excellent, primarily at portraying the experience of the grunt on the ground, who is almost wholly divorced from the geopolitical, ideological or commercial aims of the instigators of the conflict. The soldiers float sardonically above the entirely predictable self-inflicted military defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan in which thousands of lives were lost and hundreds of billions if not trillions of dollars wasted. To maintain their realism both books of necessity refreshingly poke fun at such things as university discrimination policies, relationship dynamics, and bureaucratic niceties. Veterans, given the unquestionable nature of their subjective experience, probably enjoy the most leeway when it comes to contemporary shibboleths. You weren’t there, man!

Both also effectively show the commodification of veteran’s lives by organisations at home, including charities and universities. One interesting question arising out of recent Western adventuring in the Middle East is why Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder seems to be more prevalent and more severe today than it was in the past when wars were far more bloody? One likely answer is the more extreme contrast between battle conditions and home life that exists today. Young soldiers return from Afghanistan or Iraq where they were living and fighting among a small group of friends who would kill and die for them day in and day out. Back at home there are no threats to life, and the sheer malevolent convenience of modernity, the fake politesse, reminder emails, Human Resources platitudes and doughnuts in the staff room, break hardened warriors in a way battle never could.

The standout story in Redeployment, which is also the most humourous, “Money as a Weapons System”, is set after the major conflict is over and the US is funnelling its money and energy into rebuilding “civil society”. The protagonist of the story is tasked with finding a use for baseball uniforms and equipment donated by an American mattress magnate who dreams of bringing Iraq into the liberal world order by teaching them to love the sport. It worked for Japan, he reasons. The reality on the ground in Iraq is, uh, rather different. To get anything done at all the protagonist must negotiate several untrustworthy local power structures that have conflicting goals and are all to varying degrees scornful of American interference, using the occupation to finance their own short-term goals.

Moreover, most of the Americans are wholly cynical about the chances of “bringing democracy”. The result is an environment where no one believes in the mission, no one is punished for failure, and nothing productive can happen. The mattress magnate, the one true believer, demands photo evidence that his philanthropy has not been in vain, which the protagonist eventually obtains for him in surreal circumstances.

Dirt Cult takes the form of a more traditional novel. On a break before a tour of duty in Afghanistan Tom Walton, a soldier from Oklahoma, meets his manic pixie dream-girl Amy, a dancer in a Montreal strip-club. the stripper who shouldn’t be, who somehow lets the lifestyle slide off her without dampening her enthusiasm for life. The two improbably hit it off talking about books and movies and promise to meet again when Walton returns from his tour, leading to a drawn-out long-distance relationship that provides the book with its dramatic arc.

Klay’s imagination is more calculating, more sophisticated; every violation of literary decorum is compensated for by a nod back to it. One story, for example, features an American soldier who is a Coptic Christian native Arabic speaker whose father becomes a Fox News junkie Bush fanatic, who tries to appease the sensibilities of a female Muslim student at his university. Klay knows exactly how far he can go with his triangulation of identity and with his Marines’ rough talk, exactly where the true boundaries of speech are. Finlay, by contrast, has no one to placate, and writes like a man “already dead” to borrow a phrase from Houellebecq.

The difference between the two books ultimately comes down to what we might call polish. Redeployment is good writing trying to be good writing that knows it’s good writing, and ultimately, for all its anti-PC asides and self-awareness, feels calculating and lifeless, too much touched by the workshop. Dirt Cult by contrast needs some pruning and a copy edit, but it burns raw through the page. It feels amateurish in the way Dostoevsky can be maddeningly amateurish.

Although both books feature explicit violence, neither are anti-war per se. There is hardly any moralism in relation to violence. In this both books have echoes of Ernst Junger’s hymn to warfare Storm of Steel, whose most striking feature it it’s author’s zest for the fight. War persists in part because some men find it extremely pleasurable. In Redeployment soldiers who play Call of Duty in their downtime from patrols, using simulated war to recharge from real war.

When Walton experiences his first real battle he reflects:

This was a fire roaring hot enough to burn away the bullshit that had been spoon-fed to him to stunt his growth in the name of setting him free. This was the smell of bullets breathing, and the dry Afghanistan air drinking the fresh wet blood from the last thought of the newly dead Haji lying on the ground. This was the altar where he could pay for everything he’d ever loved. This was death making life real.